(by Giuliana Rogano)

At the first floor on the white wall, in a showcases of dark wood, we read:

TIME

“In “Physics” Aristotle makes a distinction between Time and the single moments he describes as the “present”. Single moments are – like Aristotle’s atoms – indivisible, unbreakable things. But Time is the line that links them. My life as taught me that remembering Time – that line connecting all the moments that Aristotle called the present – is for must of us rather painful. However, if we can learn to stop thinking of line corresponding to Aristotle’s Time, treasuring our time instead of its deepest moment, then lingering eight years at our beloved’s dinner table no longer seems strange and laughable. Instead, this courtship signified 1593 happy nights by Füsun’s side. It was to preserved this happy moments for posterity that I collect this multitude of objects large and small that once felt Füsun’s touch, dating each one to hold it in my memory.”

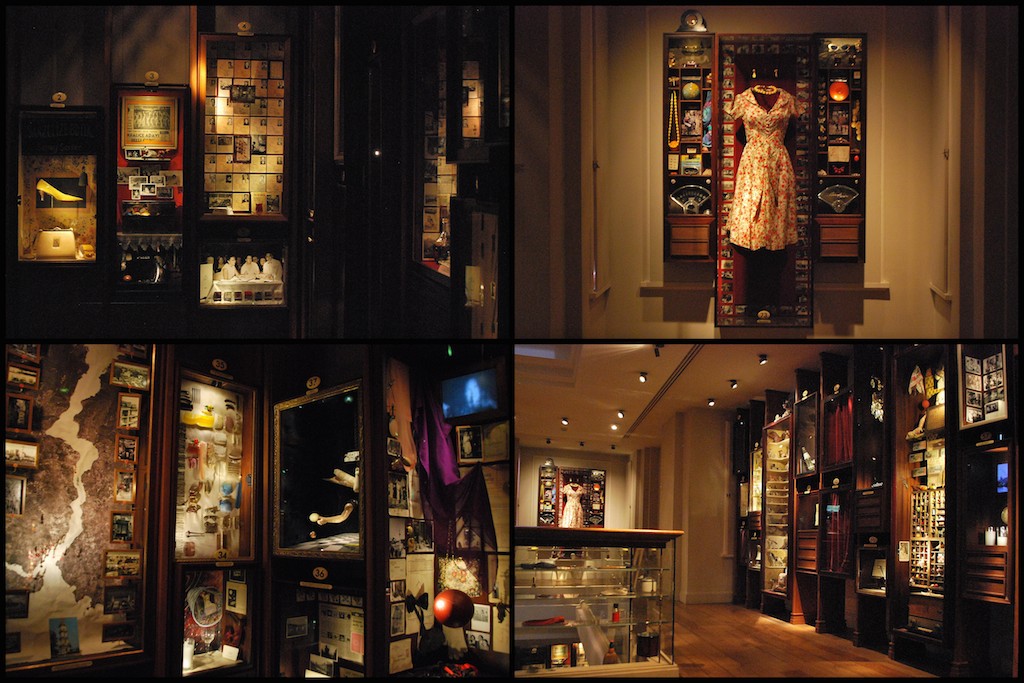

The Museum of Innocence is located in a building with three floors of 1897, completely renovated, in the district of Çukurcuma. Here between 1976 and 1984 lived their love story Kemal, offspring of a wealthy family stamboulians next to a good marriage and Füsun, the beautiful cousin, poor and impossible to marry according to the criteria of good Turkish society of the seventies. For eight years Kemal collects every type of object to remember the moments spent with her: hair clips, pins, handkerchiefs, newspaper clippings, postcards, glasses and cups still full of chai and coffee, some pieces of sweets, cigarette butts, a beautiful white dress with colored flowers as shown in a showcase accompanied by a pair of earrings and a necklace, letters and drawings, watches, photographs, a map of the city and the Bosphorus. Kemal retains everything, not to lose any of the happy moments spent together and to realize, finally, a museum dedicated to the beloved Füsun. A moving collection, delicate, tender, meticulous, bordering on the obsessive, small simple objects, which accompanied their love story. And on the top floor, the penthouse, the room where Kemal slept, usually.

And then, between the showcases, an anatomical table “to show the points where my suffering love in those days was manifested, sharpened and spread” marking them “on the image depicting the internal organs of the human body in the billboard of Paradison, a painkiller drug that, at that time, I had seen in the windows of the pharmacies in Istanbul.“

Orhan Pamuk, the writer turkish Nobel Prize in 2006, has thougth and realized the Museum in nearly 15 years, finding between markets and junk shops, or even by commissioning, paintings and design objects, to recreate the atmosphere of the City. About 1500 objects are exhibited in 83 windows, one for each chapter of his book. The Museum is a fiction, Kemal and Füsun are the characters of the novel by Pamuk and they have never existed, but there was obviously Istanbul in those years, and those objects are the representation. The exhibition is a faithful reproduction of what Kemal has designed and that Orhan Pamuk has created, but it is also primarily a way to tell Istanbul, a representation of the City at the end of the 70s of this century.

You can do a novel from a museum? Or you can make a museum from a novel? Maybe so, but in this case neither assumption is correct: the Museum and the Novel have been conceived and created simultaneously. Pamuk began collecting and collecting real items for a false story and he collected the objects while he wrote his story and he wrote his story, collecting objects.

At the entrance of the museum, which is like entering a house where you feel guests, we find the “Modest Manifesto for Museums” to immediately clarify the value that Pamuk gives the museum, whose future, very different from the rhetoric of the great national museums in which there is no room for the desires and curiosity of the individual, “resides in the privacy of our homes.”

“It was the happiest moment of my life, and I do not realize. If I knew, if I had known then, I would have been able to preserve that moment and perhaps things would be different? Yes, if I had guessed that it was the happiest moment of my life I never would have missed a happiness so great for anything in the world.“(Kemal, incipit of “The Museum of Innocence” by Orhan Pamuk)

(Photo credit: Progetto Mediterranea – © all right reserved – phgiulianarogano)

Leave A Comment